Research

Overview

My research interests focus on improving our understanding of the Earth System and how it works/worked in 'deep time', many millions of years ago, In particular, I am curious about the myriad ways in which Life and the physical Earth System have interacted in the past, how the do so in the present, and how they may do in the future. Most of my academic work to date has focused on the early Palaeozoic, from about 540 to 420 million years ago (Ma), when complex animal-rich ecosystems became firmly established throughout the oceans. More recently, I have begun to dive a little deeper into Earth's past to work on a project that spans the Ediacaran-Cambrian transition, capturing the interval in which we find the first recognisable animal fossils. Earth's physical environment underwent a series of dramatic changes through this interval; some oscillatory, and some irreversible (or, at least, not yet reversed). In trying to quantify the magnitude of these changes and what factors might have driven them, I look for fossil organisms and fossil chemistries that might be able to shed some light here. As an aside, I have a keen curiosity for the mechanisms behind the exceptional preservation of exquisite biological detail in animal fossils that we find throughout the geological records. I try to approach all of these problems with a combination of geological data, collected in the field, and numerical models to try to interpolate between and mechanistically explain these geological data.

Early Palaeozoic climate

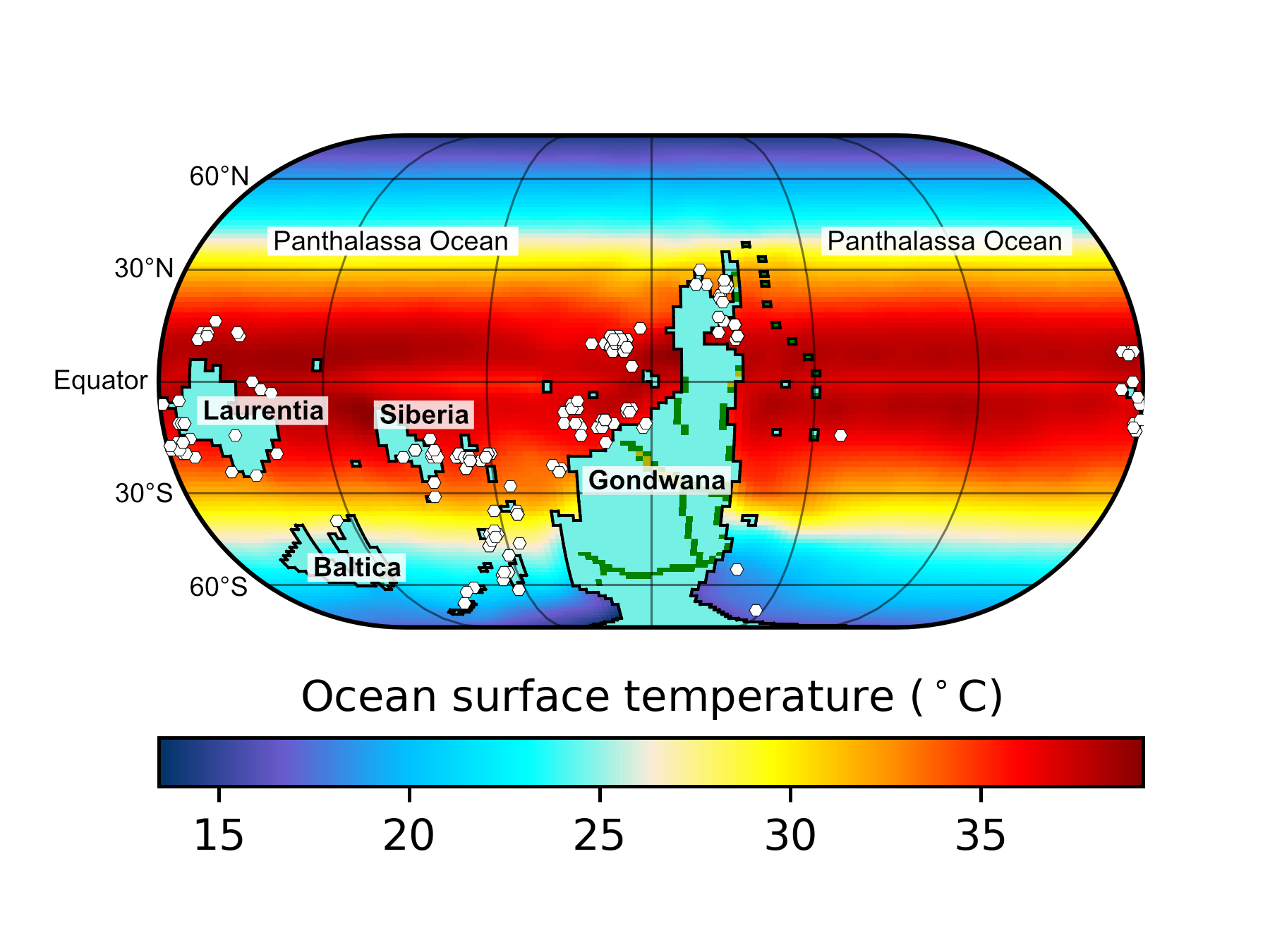

My main research focus is on understanding Earth's physical environments and climate in 'deep time'. 'Deep time' means different things to different people, but I tend to think of real deep time as being pre-Mesozoic - i.e. before about 252 million years ago, a world before the dinosaurs and very different to the one we know today. I particularly work on the state of the Earth during the Cambrian Period, 540-485 Ma, when many of the modern animal phyla first appear in the fossil record. To do this, I try to combine quantitative and semi-quantitative data from the geological with numerical model simulations to try to put some realistic numbers on Earth's condition. This was the subject of my PhD research at the University of Leicester, and of my two biggest papers to-date.

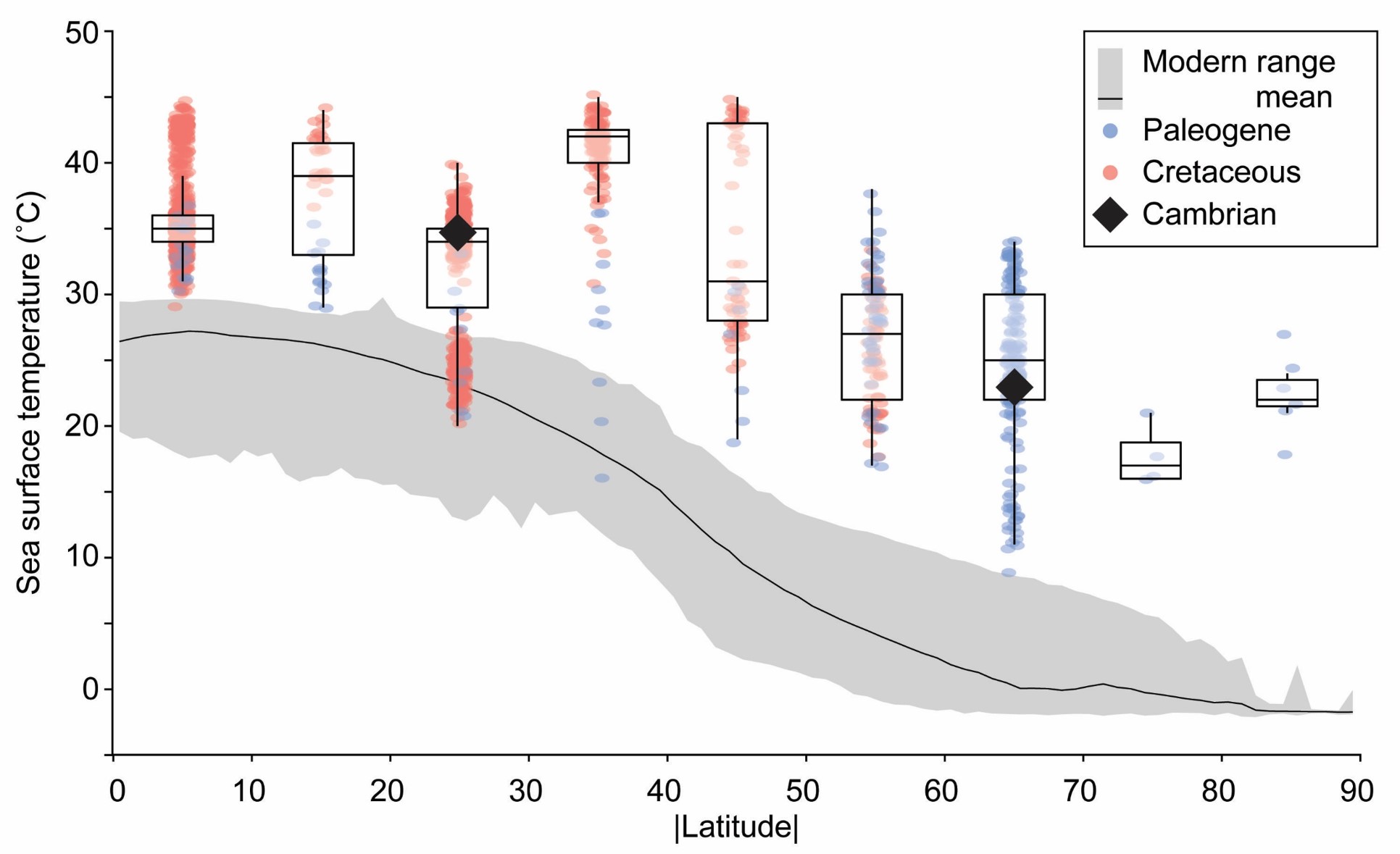

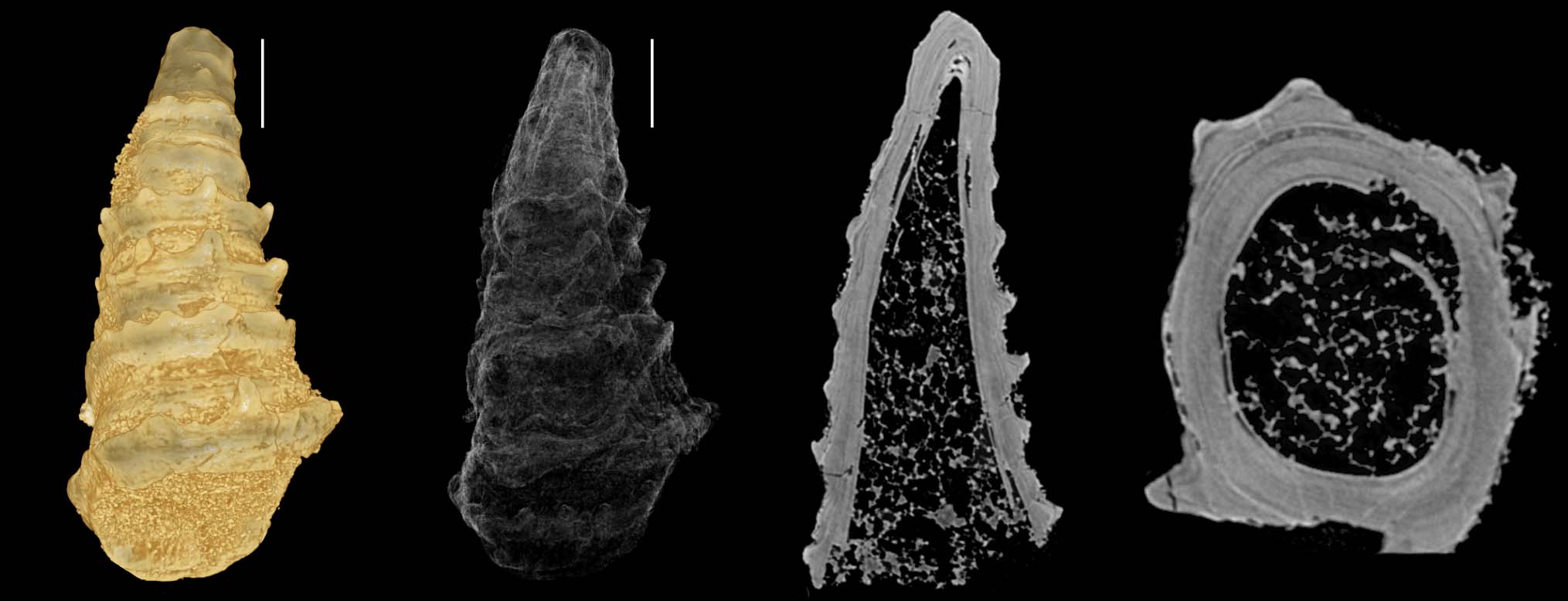

During my PhD I developed the use of phosphatic 'small shelly fossils' (SSFs) as new source of numerical palaeoclimate proxy data for the early Cambrian Period. These phosphatic SSFs can have extraordinarily well preserved chemistry, include the different isotopes of oxygen in their phosphate skeletons. This means that we can use the ratio of heavy (18O) to light (16O) oxygen in these fossils as palaeo-thermometers to 'take the temperature' of Cambrian oceans over half a billion years ago. The first data to come out of this approach suggest that the Cambrian Epoch 2 world was a warm greenhouse world, similar to the greenhouse worlds of the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods.

Also as part of my PhD research, and continuing since then, I have tried to use semi-quantitative records of palaeoclimate to better constrain Cambrian climates. Climatically sensitive rock types are rocks that form only under specific ranges of climate conditions, such as above/below temperature or precipitation thresholds. One example is glacial tillite which only forms in the presence of land ice. Deposits of climatically sensitive rock types can be compared with climate model simulations of Earth's climate to try to find the 'best-fit' climate to explain the observed geological data.

Small Shelly Fossils - the evolution of biomineralisation

The 'small shelly fossils' (SSFs) are more or less exactly what they sound like - fossils of shelly organisms that are quite small - and they have rather intricate forms. However, as Stefan Bengtson pointed out in 1994, the term 'small shelly fossils' is used for fossils that "are not always small, ... commonly not shelly and ... might equally well apply to Pleistocene periwinkles." In other words, it's not a very useful description for what are really very interesting and useful microfossils. In practice, the term 'SSFs' is generally reserved for small (<20 mm) shells or skeletal elements found in Cambrian-age limestones using standard micropalaeontological processing methods. Often, SSFs are preserved as calcium phosphate, though many of these organisms originally had calcium carbonte skeletons that have been replaced by phosphate.

Biologically-speaking, the SSFs are an eclectic mix of different animal phyla, including arthropods, molluscs, brachiopods, and sponges. Many of these are considered to be 'stem-group' members of these phyla, meaning that they are quite distantly related to all living forms of these phyla. SSFs have a global distribution and have been found on every modern continent (and on every palaeocontinent that existed in the Cambrian Period). However, it is really hard to correlate deposits of this age around the world, and it is not at all clear how SSF distributions changed over time, and indeed why they seem to become much much less common in the fossil record after the early Cambrian (from about 509 Ma onwards).

Early Palaeozoic fossils

I have been fortunate enough to be able to work with a whole range of mostly invertebrate fossils from the Ediacaran of Newfoundland to the Cretaceous of Dorset. My earliest formal research was on erosion monitoring of the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site in Dorset where we were trying to understand how the iconic 'Ammonite Pavement' at Lyme Regis was breaking up. My university-based research has focused mostly on the early Palaeozoic interval (the Cambrian, Ordovician, and Silurian periods), and I have been able to study a whole range of invertebrate fossils from this time. Recently I examined a suite of Upper Ordovician graptolites and ostracods (and a few other groups) from Vietnam with the aim of working out exactly where in the Upper Ordovician they were (Katian Stage, we decided in the end). I am currently working on an interesting suite of Cambrian SSFs from Morocco.

Exceptional fossil preservation

I have been fortunate enough to work with some exceptionally beautiful fossils that preserve the soft and non-mineralised parts of long-extinct animals. My good fortune here has extended to being able to describe two new species of non-mineralised arthropod, one from the Cambrian Period and one from the Ordovician Period. These exquisite fossils have helped to fill gaps in our understanding about the nature of the diversification patterns of early animals. These days, I am more interested in understanding the processes that lead to such exceptional preservation, and what factors control these processes, than the fossils per se - but I am always happy to see a beautiful fossil!

Teaching & Pedagogy

Since starting to teach my own classes as lectures, practicals, and in the field, I have become increasingly interested in ideas about what makes effective teaching practice. More details of my teaching practice can be found on the Teaching page of this site, but I wanted to share some thoughts on my own practice here. Partly (perhaps mostly) because it is what most interested me, I have always considered practical work to be a crucial part of a scientific education, in particular becuase working science is driven by curiosity and aiming to working things out or discover things. In the geosciences,this includes field work. However, practical-focused teaching has the potential to be a barrier to engagement with science in a world where such barriers really needn't exist. In particular, I have tried to increase the accessibility of my field teaching and that of the whole department over the last few years. Where necessary, this has involved developing high quality alternatives to existing field courses including developing the Rock Garden - a mechanism for teaching field skills on campus - and creating 3D virtual outcrops of some of the most important sites on the UGent Welsh Basin field course. Neither of these 'local' teaching tools should be considered full substitutes for 'real-world' field work, but they provide additional training opportunities for learning and honing field skills in more accessible settings.